Where do the ATMP RA/CMC challenges arise?

Network

Prioritization and strategic decisions early on (Quality-by-Design, Lean thinking, frontloading) are especially relevant for expensive production processes with low throughput of batches such as ATMPs. Prioritization comes back to de-bottlenecking existing facilities and focusing on increasing the number of batches per year. However, most ATMP development companies do not have production facilities for clinical or commercial production and thus rely extensively on CDMOs. Selecting several CDMOs to find good partners early on is important to have sustained access to ATMP production capacity, exchange ATMP production knowledge (tech transfer) and assist in balancing the R&D portfolio. Having a well-rounded network is most likely more important than a facility or a product itself. Furthermore, it helps to understand how to build a new facility and bridge the time needed to have a cGMP-ready facility.

Improvement of process steps

After securing and increasing production capacity, it is important to improve process yields or process steps. For example, in vivo CAR-T-cell therapy by nanoparticles, exosomes, or viral vectors removes expensive production steps compared to ex vivo CAR-T products (i.e., YescartaTM, KymriahTM, BreyanziTM). Also, process intensifications on bioreactor designs for USP and continuous DSP equipment have come available for GMP productions, such as the iCELLis® fixed-bed bioreactor that is used for Zolgensma® (Novartis), the scale-X™ fixed-bed bioreactor with automated in-line TFF concentration, or the CliniMACS Prodigy® for automated adherent cell culture (Miltenyi Biotec). They may need to follow the new ICH Q13 guideline on continuous manufacturing of drug substances and drug products by July 2023 (EMA). What is more, a complete continuous production platform may come available as shown in proof-of-concept studies on continuous biosimilar antibody production (BiosanaPharma B.V.), viral vector production by a continuous tubular bioreactor (CTB) system with a continuous DSP (ContiVir), or a fully automated platform design for Tissue Engineered Cartilage Products (Haeusner et al., 2021).

Facility of the year

Artificial Intelligence for intelligent sensing (e.g., by Raman spectroscopy analysis) or machine learning from design-of-experiments push process intensification and process understanding. These process analytical technology (PAT)-developments will trigger many new developments. For example, efficient in-/online live monitoring by PAT may become suitable for Real Time Release Testing (RTRT) or interim batch release for ATMPs reducing the need for complex hold-time studies or stability studies. Recently, the ISPE Facility of the Year Award 2022 was awarded to Takeda for their groundbreaking end-to-end supply chain management of an allogeneic mesenchymal stem cell therapy production showcasing that real-time batch release, innovative manufacturing designs, and rapid testing enables the processing of products with a shelf-life of only 48 hours (2022 Category Winner for Supply Chain. ISPE)!

This facility as well as many CAR-T facilities profited from implementing Manufacturing Execution System (MES) on top of an efficient Enterprise Resource Planning generating electronic batch records, real-time reporting, and oversight on shop floor operations. It enables the processing of many batches in parallel. MES-driven manufacturing is the standard at the CAR-T manufacturing giants such as Kite/Gilead, Janssen/J&J and BMS when processing >400 batches in parallel and releasing >40 batches per day in one facility. At such facilities, batch records are starting to be reviewed for exceptions (instead of a full review), and deviations are efficiently pre-prioritized. MES enables team managers to restart failed batches sooner, and QPs can release batches before deviations have been closed or the product expires. It helped the CAR-T manufacturing giants to reduce failure rates to below <5% and out-of-specs to 10-20%. Consequently, automation and continuous manufacturing – see also Pharma 4.0TM (ISPE) – may reduce cell therapy Costs of Goods (COGs) by >70% by reducing operator use, decreasing the footprint, increasing batch success rates (less contamination risk), and better manufacturing oversight.

Incremental improvements

Also, 2nd or 3rd generation chromatography resins or new chromatography columns (e.g., monoliths) have immense potential to drastically increase yield and purity. This has been especially relevant for increasing rAAV DSP efficacy. Also, automating manufacturing in RABS reduces open handlings in flow hoods and reduces the number of operators needed. Further, production cell line selection or changing to plasmid DNA-free viral vector productions (see, for example, TESSA™ technology by Oxgene) can reduce productions costs. Nevertheless, incremental improvements (Lean Six Sigma thinking) for example, selecting cheaper chromatography resins, more efficient buffers and cell media, reduce waste, better DNA transfection agents, and improved DNA removal enzymes can also make the difference in having a viable manufacturing site and reduced COGS. Some processes at an early stage (clinical phase I/II) may allow shortcuts by using non-GMP material to reduce cost. But the drawback of producing, for example, viral vectors with non-GMP starting material introduces risks to reference materials and the product description that can be challenging to tackle at later time points.

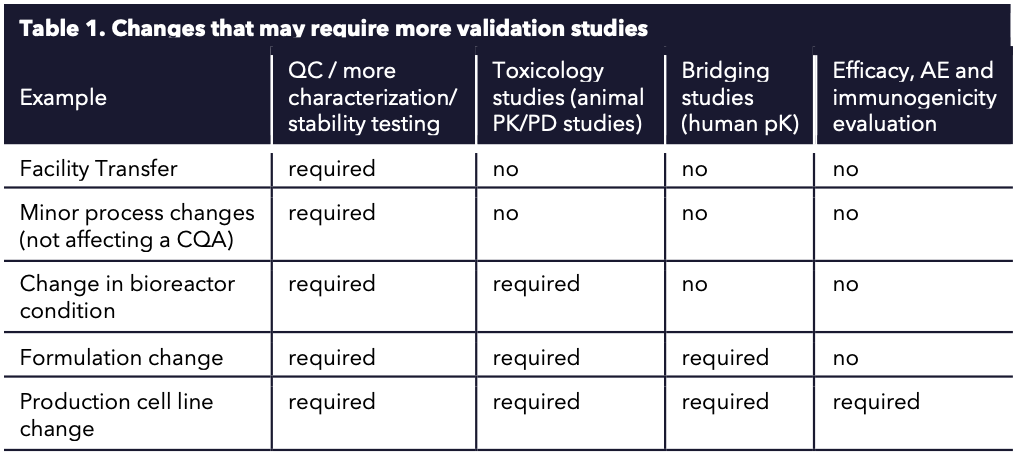

The incremental improvements are especially difficult to realize in a tightly regulated GMP environment. Many of the suggestions may trigger comparability studies and method-bridging studies (Table 1). For example, changing production cell lines once clinical trial phase I studies have started is not preferred because it would trigger new toxicology studies. After all, the product may have a different immunologic profile or slightly different infection profiles. Nevertheless, changes in drug manufacturing process development are inevitable as one (or the field) learns more about the manufacturing process and the analytics. Some of the more often occurring ATMP CMC changes are:

- Phase I: Process/Formulation changes that may require added testing in animals.

- Phase II: Equipment changes, process improvements and lot sizes change (Scale-up) for better impurity profiles or recovery requiring comparability studies.

- Phase I/II: Reagents changes, more sensitive assay methods, or industry assay standards change requiring appropriately designed method-bridging studies.

- Phase III: Any change is generally avoided and pushed back after market authorization.

- Phase III: A product that successfully passed through phase I/II going into III may be already reappropriated to other diseases (new phase I/II studies in another patient pool)

- Post-approval: Tech transfer to new facilities (scale-out).

Table 1. Changes that may require more validation studies.

To conclude

The accelerated technological improvements in the ATMP space enable a faster transition from the lab bench to commercial production. For example, the FDA or EMA fast-track programs and combining clinical trials (I/II and II/III studies). But speeding up requires having trust in your cGMP facility and people, an early and thorough CMC strategy, and continuous training on cGMP rule(s) changes. The RA and the CMC technical challenges need to be dealt with head-on, preventing changing manufacturing processes that can lead to serious delays, such as needing to change production cell lines or moving to a process intensification process in clinical trial phase II/III studies. Also, ATMP cGMP may be less defined than the general manufacture of pharmaceutical products but only to enable risk-based approaches stemming from individual production processes that, for example, may not be suitable for sterile filtration. It should rather trigger how one can improve sterile production by RABS and closed production processes. Or how to improve data on RTRT by PATs and machine learning. Consequently, with the right resources and expertise, the industry will be able to overcome these challenges and continue to provide the latest treatments to patients in need.

References

Haeusner S, Herbst L, Bittorf P, Schwarz T, Henze C, Mauermann M, Ochs J, Schmitt R, Blache U, Wixmerten A, Miot S, Martin I, Pullig O. From Single Batch to Mass Production-Automated Platform Design Concept for a Phase II Clinical Trial Tissue Engineered Cartilage Product. Front Med (Lausanne). 2021 Aug 13; 8:712917. Doi: 10.3389/fmed.2021.712917. PMID: 34485343; PMCID: PMC8414576.

2022 Category Winner for Supply Chain. Website: 2022 Category Winner for Supply Chain | ISPE | International Society for Pharmaceutical Engineering